No previous BJP election campaign has been so singularly centered around one individual: Modi’s projection exceeded even Indira Gandhi’s strategy of orienting the 1971 campaign around her personal appeal.

As the 2024 general election campaign winds down, it has been nothing like we anticipated. Many believed it would be a straightforward victory for the BJP, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi treating the campaign as a mere formality before his third term. We expected Modi to focus on his achievements, dismiss his opponents, and bask in the adulation of his supporters before returning triumphantly to Race Course Road and South Block.

As the 2024 general election campaign winds down, it has been nothing like we anticipated. Many believed it would be a straightforward victory for the BJP, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi treating the campaign as a mere formality before his third term. We expected Modi to focus on his achievements, dismiss his opponents, and bask in the adulation of his supporters before returning triumphantly to Race Course Road and South Block.

Contrary to expectations, the BJP launched the campaign with aggressive pre-emptive strikes against its opponents. The Congress faced frozen bank accounts, two sitting Chief Ministers were arrested, and non-BJP politicians across India lived in fear of raids and arrests.

Another surprising development was the unprecedented scrutiny of the Election Commission. Previously, even when the integrity of elections was questioned, the Commission itself was seen as impartial. This time, however, the Commission faced widespread suspicion and criticism from the Opposition, which viewed it as a compliant tool of the ruling party. The Commission’s vehement denials and accusatory statements against the Opposition may have inadvertently bolstered allegations of bias.

Regardless of one’s political stance, the decline in the Election Commission’s credibility is detrimental to Indian democracy. The Commission blames its critics, while the critics blame the Commission. Either way, democracy suffers.

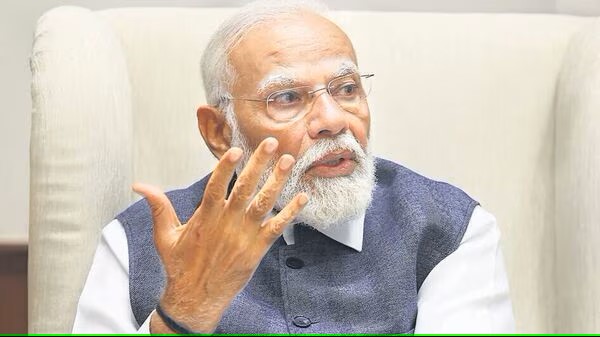

The BJP campaign was markedly personalized. Modi, undeniably the BJP’s greatest asset, was the focal point. The extent to which this campaign was centered around him surpassed even Indira Gandhi’s 1971 campaign.

Interestingly, this was not the imperial Prime Minister many expected. Instead, we saw an aggressive, emotionally charged Modi, more focused on his role than ever before. He frequently referred to himself in the third person and did not shy away from Hindu-Muslim rhetoric, a departure from his usual approach in general elections.

One theory is that Modi intensified the sectarian rhetoric after low turnouts in the first phases, possibly to energize BJP workers or to attract more votes. Once confident of his victory, he attempted to distance himself from sectarian politics, but the Hindu-Muslim theme persisted, with references to ‘love jihad’ and other divisive issues.

The political landscape also saw Rahul Gandhi countering Modi’s narrative by accusing the BJP of upper-caste bias and advocating for a caste census and the advancement of marginalized caste groups. Additionally, Congress adopted a class-based rhetoric, reminiscent of Indira Gandhi’s 1971 campaign, accusing the BJP of favoring the rich and pledging to help the poor.

The BJP seemed taken aback by the Congress’s class-based attacks, with Modi unexpectedly alleging that the Ambanis and Adanis had funded the Congress.

Despite the twists and turns, few doubt that the BJP will form the next government with Modi at the helm. However, this campaign underscored the unpredictability of Indian politics, where new issues can emerge unexpectedly, and campaigns rarely unfold as anticipated.

This campaign has not favored the Indian electoral system. The extreme rhetoric, the strategic use of investigative agencies against the Opposition, and the pervasive distrust of the Election Commission are troubling trends. Ultimately, the health of Indian democracy is more crucial than the success of any political party.

India needs fair, non-hyphenated, and questioning journalism, packed with on-ground reporting. ThePrint – with exceptional reporters, columnists, and editors – is doing just that. Sustaining this needs support from wonderful readers like you.