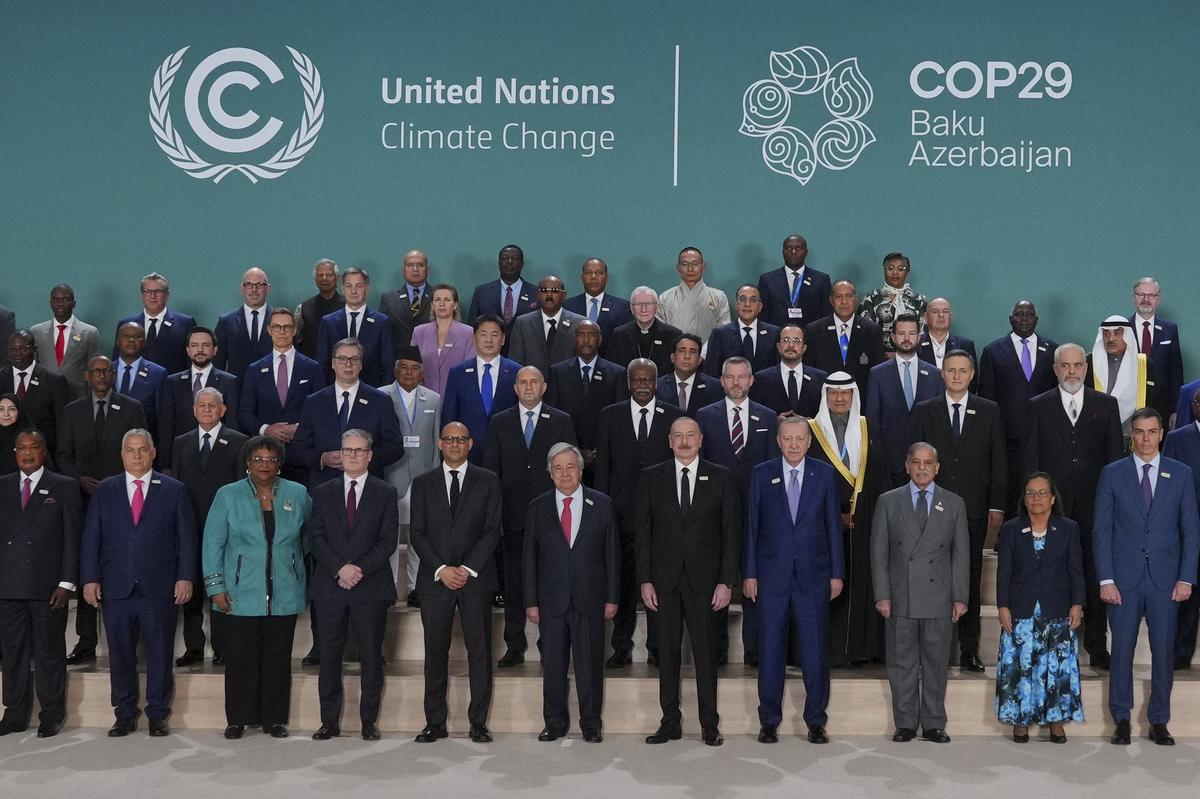

Delegates at the COP29 climate summit, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, on November 12, 2024, voted to approve a long-awaited agreement that finalizes the framework for a global carbon market. This market will allow countries and companies to trade carbon credits—certified reductions in carbon emissions—as part of their efforts to meet climate targets outlined in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

The agreement stems from Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which offers two pathways for carbon trading: one for bilateral agreements between countries (Article 6.2) and another for participation in a global carbon market (Article 6.4). The market will enable countries to trade carbon credits, with the price of credits influenced by the emission reduction targets and caps set by individual nations.

The agreement stems from Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which offers two pathways for carbon trading: one for bilateral agreements between countries (Article 6.2) and another for participation in a global carbon market (Article 6.4). The market will enable countries to trade carbon credits, with the price of credits influenced by the emission reduction targets and caps set by individual nations.

Although the operational framework for the carbon market has been largely in place since 2022, unresolved issues surrounding the transparency and authenticity of carbon credits have delayed final implementation. Key concerns included ensuring that carbon credits are genuinely linked to emission reductions, and that the origin and validity of these credits are clear and transparent.

In the lead-up to COP29, UN bodies had worked on draft guidelines to address these concerns. Despite some remaining reservations, there was optimism that a functional global carbon trading system would begin to take shape, with the first UN-sanctioned carbon credits expected to be available by 2025.

A significant challenge in implementing carbon markets is ensuring accurate accounting. For example, if a developed country finances an afforestation project in a developing nation that reduces emissions by 1,000 tonnes, questions arise about whether those saved carbon credits should be counted by the developed country or the one where the project is located. Clarifying such issues is crucial for determining how carbon credits can be used to meet global climate goals.

India, for example, has committed to reducing its emissions intensity by 45% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels, as part of its NDC. It also plans to create an additional 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of forest and tree cover by the same year. These efforts could be bolstered by the trading of carbon credits under the new market.

COP29 President Mukhtar Babayev highlighted the importance of the agreement, calling it a “game-changing tool” that would direct resources to developing countries. While the agreement is a significant step forward, Babayev cautioned that further work remains to ensure the full implementation of the carbon market.

Experts like Vaibhav Chaturvedi, an energy economist and carbon market specialist at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), noted that while the decision on Article 6.4 is a major breakthrough, the methodologies for implementing the system are still being finalized. He also stressed that the focus should not solely be on carbon markets, as the new global climate finance goal, known as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), must also be prioritized. The NCQG aims to scale up climate finance for developing countries, with an updated target expected to be in place by 2025.

U.N. Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell emphasized that a new global climate finance goal is crucial to supporting nations that cannot afford to rapidly reduce emissions on their own. “Climate finance is not charity—it is in the self-interest of all nations, including the wealthiest,” he said.

The approval of the global carbon market marks a pivotal moment in the effort to curb global emissions, but much work remains to ensure that it can operate effectively and equitably, particularly for developing countries.