The India-Tibet-China Triangle: A Forgotten History Behind a Modern Border Dispute

History in politics isn’t just a record of the past—it’s often a tool to shape present narratives. In the case of India, Tibet, and China, centuries of interactions—diplomatic, cultural, and military—have shaped a complex geopolitical triangle that still influences current border tensions, particularly over Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh.

1. Ancient Links and Expansionist Paths

In Indian texts, Tibet was known as Trivishtap, a land connected with ancient Yaksh culture and Buddhist kingdoms. While China remained confined behind its Great Wall for centuries, its territorial ambitions eventually reached Tibet and even extended towards regions traditionally tied to India.

The real political game among India, Tibet, and China began around the 7th century CE. Kashmir’s powerful dynasties frequently extended their control over Ladakh and even parts of western Tibet. A key figure in this expansion was Lalitaditya Muktapida, an 8th-century ruler often called “Alexander of India.” His campaigns pushed Kashmir’s influence into Tibetan territory, laying early claims over areas like Aksai Chin and Ladakh—claims documented in Indian texts like Rajatarangini and Chinese records.

2. Tibet-Nepal Conflicts and China’s Entry

In the late 18th century, Tibet clashed with the Gorkha Empire of Nepal. Two wars (1788–89 and 1791–92) resulted in Qing China intervening militarily to defend Tibet. The Treaty of Betrawati (1792) forced Nepal to pay tribute to both Tibet and China. This marked Tibet’s entry into China’s sphere of influence, giving Beijing a historical excuse to later claim sovereignty over the region—a point still echoed in modern Chinese narratives.

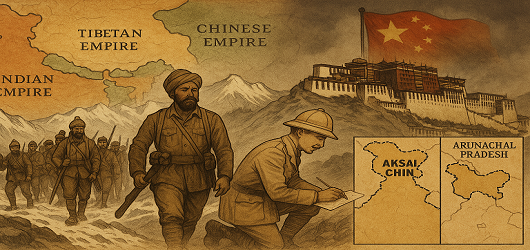

3. General Zorawar Singh’s Campaigns

From 1834 to 1841, General Zorawar Singh, under Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu & Kashmir, launched successful military expeditions that captured Ladakh, Baltistan, and reached deep into western Tibet, even near Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar. Although he eventually died in battle, his campaigns cemented Jammu & Kashmir’s administrative control over Aksai Chin—making it part of the Indian state before Chinese claims ever arose.

4. British India and Border Formalization

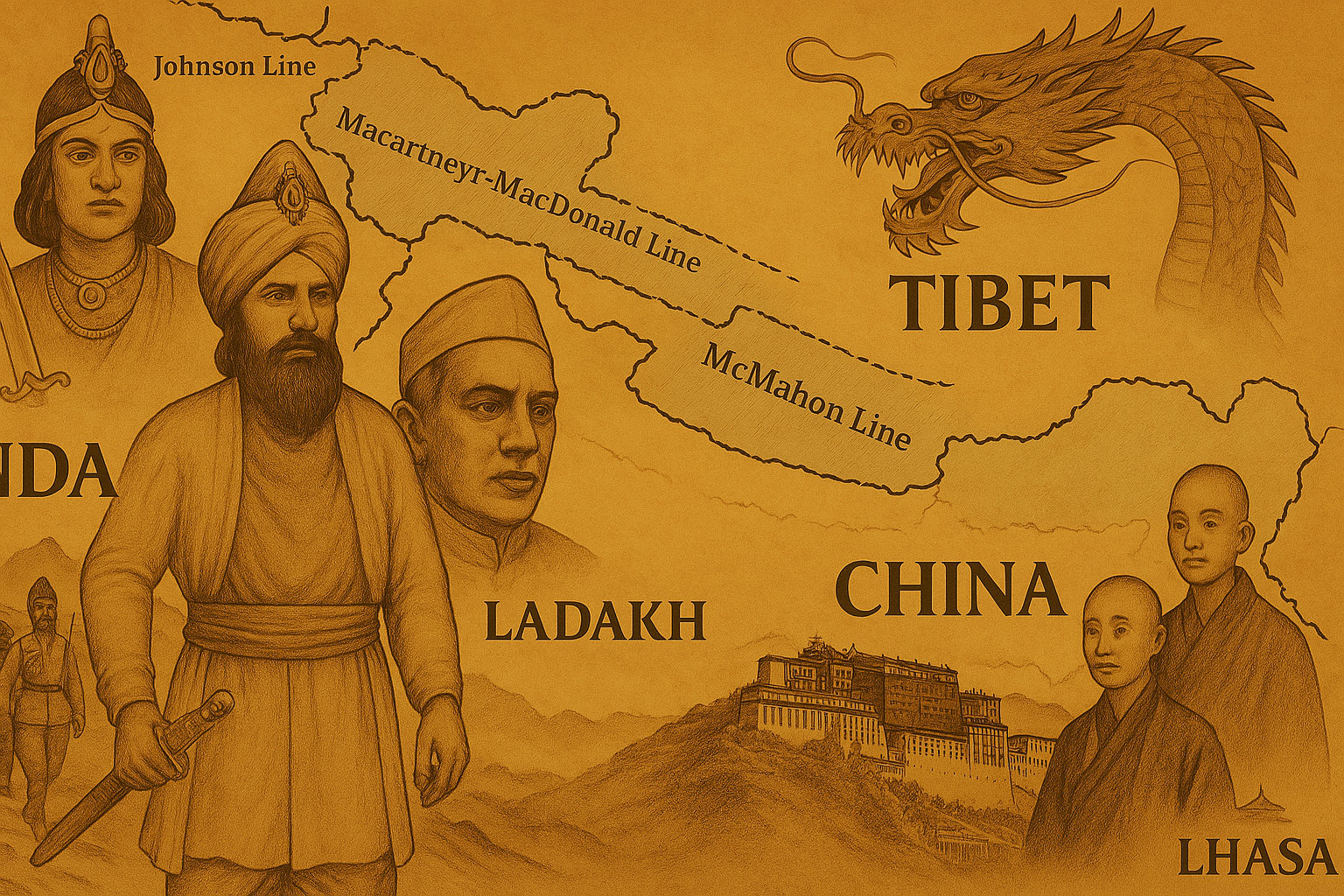

After Zorawar Singh’s death, boundary issues remained unresolved. The British attempted to define clearer borders:

-

1846 Treaty of Amritsar: After the First Anglo-Sikh War, the British gave control of Kashmir (including Ladakh and Aksai Chin) to Gulab Singh.

-

1865 Johnson Line: British cartographer William Johnson drew a boundary placing Aksai Chin within India.

-

1890 Macartney-MacDonald Line: Britain proposed a different line favoring China’s claim. Though China considers this legitimate, the British never formally adopted it.

Interestingly, no major dispute erupted until 1950—when China occupied Tibet.

5. 1906 Convention and a Shadowed Autonomy

In 1906, Britain and Qing China signed a treaty acknowledging China’s suzerainty over Tibet but preserved British India’s trading rights. This agreement placed Tibet within China’s influence without recognizing full sovereignty—laying the groundwork for future claims over Tibetan territory, including border areas like Arunachal Pradesh.

6. Tibet’s Short-Lived Independence (1911–1950)

After the Qing dynasty collapsed in 1911, Tibet declared independence in 1912. British India supported this unofficially, seeing Tibet as a buffer against Russia and China. In 1914, the Shimla Conference between British India, Tibet, and China led to the creation of the McMahon Line, marking the eastern border of India. Though China refused to accept this line, it became the legal basis for India’s claim over Arunachal Pradesh.

7. India’s Independence and China’s Invasion of Tibet

After India gained independence in 1947 and integrated Jammu & Kashmir (including Aksai Chin and Ladakh), China began its moves. In 1950, the People’s Liberation Army invaded Tibet. However, Indian leadership—particularly Prime Minister Nehru—misjudged China’s intentions.

Despite warnings from figures like Sardar Patel, K.M. Munshi, and even leaders like Swami Vivekananda and Vinayak Savarkar in earlier decades, Nehru underestimated China’s expansionist designs. His romanticized view of Indo-China solidarity led him to support China’s bid for a permanent seat at the UN Security Council—ironically bypassing India’s own chance at global leadership.

8. The Tipping Point

China began testing India’s resolve through small incursions into Tibet to gauge its reaction. Nehru’s government, weakened by poor military readiness and idealism, did not respond forcefully. Encouraged, Mao Zedong launched a full takeover of Tibet in 1950. India’s lack of action during this period allowed China to cement its control over Tibet, turning what was once a buffer state into a frontline zone for conflict.

Conclusion: Lessons from History

Modern border issues between India and China—especially over Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh—cannot be understood without this historical backdrop. Whether it’s General Zorawar Singh’s campaigns, the Johnson Line, or the McMahon Line, India’s territorial claims are rooted in a much deeper historical context than China often acknowledges.

Ignoring history has cost India strategically. Recognizing Tibet’s past autonomy and India’s deep cultural, religious, and administrative ties to regions like Aksai Chin could strengthen its diplomatic stand.

History, after all, isn’t just what happened—it’s what we remember, assert, and learn from.